The Heroes of Desegregating in Public Libraries

Public libraries are beloved community centers that offer access to computers, reading materials, and intriguing programming. But younger generations may not realize that in the thick of the Civil Rights Movement public libraries were just as segregated as the rest of the country. In fact, “the few public libraries in the South that did provide limited services to blacks often subjected them to experiences that were humiliating” (Eberhart, 2018). So in honor of Black History Month, we are going to look at those African American individuals who were crucial in desegregating public libraries.

Virginia Sit-In:

Sit-ins and other peaceful protests played important milestones in the Civil Rights Movement, particularly when fighting for equal access to public libraries. The first library sit-in occurred in August 1939 when five African American men entered the Barrett Branch of the Alexandria (VA) Public Library and requested library cards. When they were denied library cards, the men peacefully read books until the police arrested them for using a “whites-only” facility. In response to the altercation, the Alexandria Public Library opened the Robinson Library, a substandard library that, today, houses the Alexandria Black History Museum (Newseum, 2015).

Sit-ins and other peaceful protests played important milestones in the Civil Rights Movement, particularly when fighting for equal access to public libraries. The first library sit-in occurred in August 1939 when five African American men entered the Barrett Branch of the Alexandria (VA) Public Library and requested library cards. When they were denied library cards, the men peacefully read books until the police arrested them for using a “whites-only” facility. In response to the altercation, the Alexandria Public Library opened the Robinson Library, a substandard library that, today, houses the Alexandria Black History Museum (Newseum, 2015).

Greenville Eight:

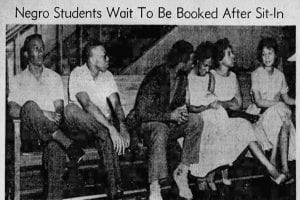

Again, on July 16, 1960 eight students, including Jesse Jackson, who later became a famous civil rights activist and minister, utilized the “whites-only” reading room” at the Greenville County (SC) Public Library because the book they needed for a school assignment was not available at the African American library. Although the librarian commanded them to leave multiple times, the “Greenville Eight” persevered. Police finally arrested the group and the library closed indefinitely so it would not be liable for discrimination lawsuits.

Again, on July 16, 1960 eight students, including Jesse Jackson, who later became a famous civil rights activist and minister, utilized the “whites-only” reading room” at the Greenville County (SC) Public Library because the book they needed for a school assignment was not available at the African American library. Although the librarian commanded them to leave multiple times, the “Greenville Eight” persevered. Police finally arrested the group and the library closed indefinitely so it would not be liable for discrimination lawsuits.

Public pressure eventually forced the library to reopen and while the city mayor refused to admit the library system was now integrated he implied it: “The city libraries will be operated for the benefit of any citizen having a legitimate need for the library and their facilities…” Due to their courage, the Greenville Eight set a precedent for other African American students fighting for their right to use public libraries.

Tougaloo Nine:

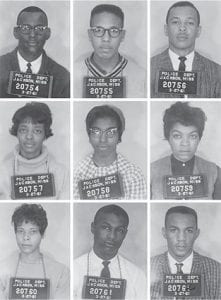

Similarly, the “Tougaloo Nine” walked into the Jackson (MS) Public Library needing to research for a school assignment and were promptly arrested and detained for thirty-six hours. At the courthouse, their one-hundred supporters were beaten by policemen and attacked by police dogs. Even so, “the brutality exercised on black people supporting the library protesters in Jackson set in motion broader desegregation activities in Mississippi” (Wiegrand, 2017).

Similarly, the “Tougaloo Nine” walked into the Jackson (MS) Public Library needing to research for a school assignment and were promptly arrested and detained for thirty-six hours. At the courthouse, their one-hundred supporters were beaten by policemen and attacked by police dogs. Even so, “the brutality exercised on black people supporting the library protesters in Jackson set in motion broader desegregation activities in Mississippi” (Wiegrand, 2017).

St. Helen Four:

Finally, on March 7, 1964 the “St. Helen Four” approached the St. Helen branch of the Audubon Public Library in Greensburg, Louisiana, where the librarian immediately locked the door. However, instead of giving up these four students returned to the library every day–even amidst protesters and harassers–and regularly drank from the “whites-only” water fountain (Wiegrand, 2017).

The first day of school at Ft. Myer Elementary School after the Brown vs. Board of Education ruling.

The first day of school at Ft. Myer Elementary School after the Brown vs. Board of Education ruling.

The bravery these protesters exhibited during such an important time in our nation’s history influenced three of the Supreme Court’s decisions that helped dismantle segregation in public libraries: Brown vs. Board of Education, which overran the “separate but equal” ruling in segregated schools with broader implications. Also, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed discrimination in public facilities, including public libraries. Finally, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 gave African Americans power in their local governments and thus in their local public libraries (A History of Public Libraries).

Thankfully, today the American Library Association (ALA)–the governing organization over all libraries in America–fully supports African Americans’ right to public library access (ALA Bill of Rights). On June 24, 2018, the governing council of the ALA “apologiz[ed] to African Americans for wrongs committed against them in segregated public libraries” and applauded those “who risked their lives to public libraries for their bravery and courage in challenging segregation in public libraries and in forcing public libraries to live up to the rhetoric of their ideals” (Eberhart, 2018). Truly, these heroes in the desegregation of public libraries played vital roles in shaping the future of our country’s libraries.

References:

Digital Public Library of America. A history of US public libraries. Retrieved from: https://dp.la/exhibitions/history-us-public-libraries/segregated-libraries/desegregation.

Eberhart, G. (2017, June 1). The greenville eight: The sit-in that integrated the greenville library. Retrieved from: https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2017/06/01/greenville-eight-library-sit-in/.

Eberhart, G. (2018, June 25). Desegregating public libraries: The untold stories of civil rights heroes in jim crow south. Retrieved from: https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/blogs/the-scoop/desegregating-public-libraries/.

Newseum (2015, February 9). Unsung heroes: Virginia library sit-in. Retrieved from: http://www.newseum.org/2015/02/09/unsung-heroes-virginia-library-sit-in/.

Wiegand, W. (2017, June 1). Desegregating libraries in american south: Forgotten heroes in civil rights history. Retrieved from: https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2017/06/01/desegregating-libraries-american-south/.